A Different Way of Reading: Gaining insights into Euripides’ Bacchae by viewing the text from a new angle

written by Claudia Kappely

After finishing work on Pliny the Elder’s Natural History for MANTO I still had plenty of hours left in my PACE internship and decided to move onto capturing Euripides’ Bacchae. As it is the text I am focusing on for my Ancient History Capstone this semester I already knew Bacchae well but was keen to approach it from a vastly different angle.

One aspect of this was collating the locations Dionysus travels via before reaching Thebes into one tie. Though his arrival in Thebes marks the beginning of a quest to share his cult with all of Greece, before the events of the play Dionysus has gained a successful following across Asia Minor. Looking at the list of places Dionysus mentions and using the mapping function of MANTO his reach as a god became much clearer to me.

Places mentioned in the description of Dionysus’ travels before arriving in Thebes (Eur. Bacch. 1-63). The blue dots mark locations using geometry in Pleiades. Image: C. Kappely, modified from MANTO.

Dionysus' response to his Theban family’s rejection of his divinity in Bacchae is extreme, violent, and comes across as somewhat irrational. However, visualising the great scope of his cult before the play makes it easier to understand.

He may be a new god to Greece, but he is not a new god altogether. Until this point he has been treated with reverence across a massive area of land. Who are his family and Thebes to deny his divinity now? It is no wonder he is angry.

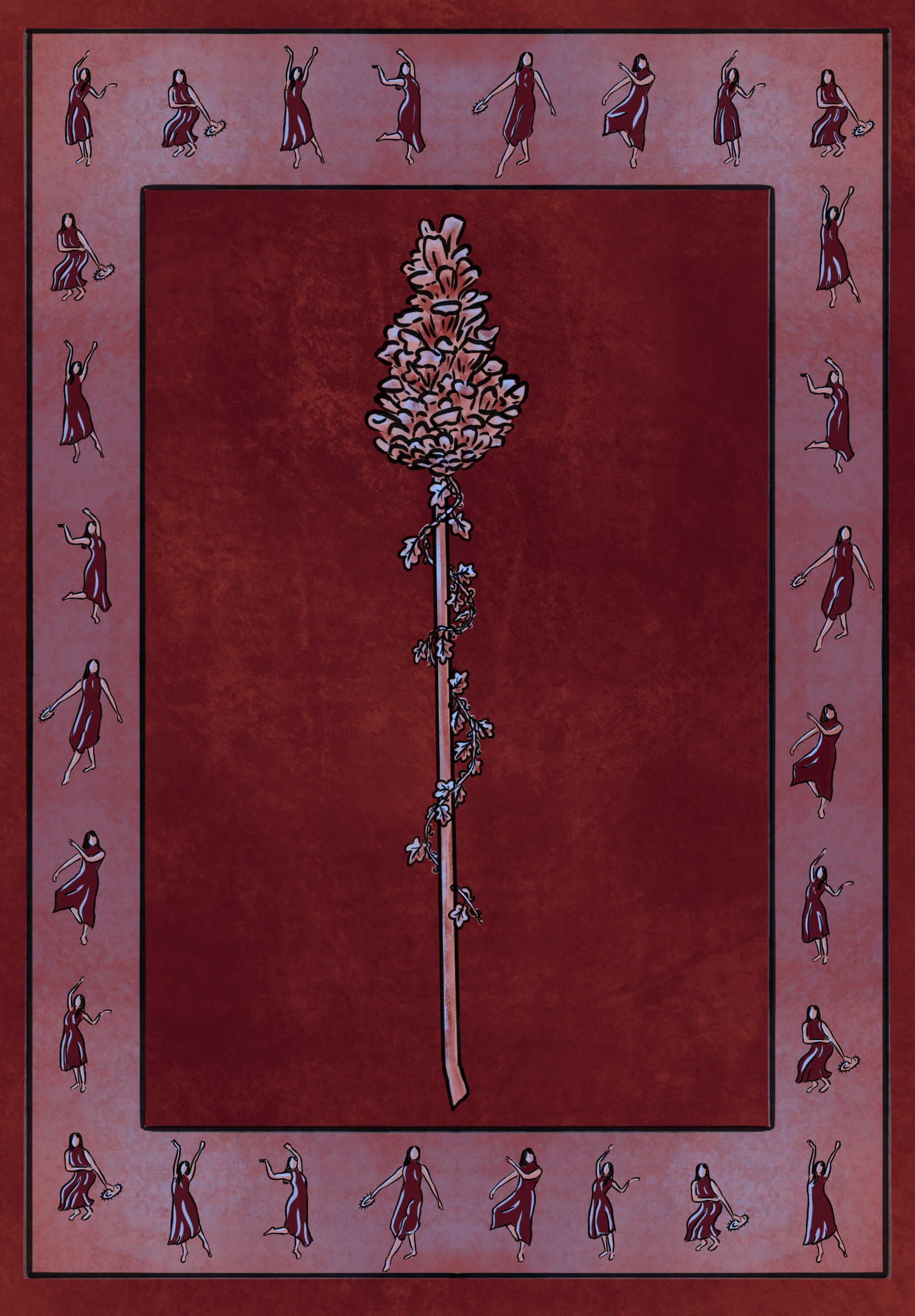

Illustration of a thyrsus, a ritual symbol of Dionysus and motif used to represent his cult over the play.

Image: C. Kappely.

A further connection that I had previously glossed over whilst reading Bacchae was that between Pentheus and Actaeon. Close reading to gather data for MANTO with a focus on names and connections highlighted to me how closely their myths are intertwined.

They are cousins, sharing Cadmus as a maternal grandfather (lines 229-230) and the manner and reasons for their deaths reflect each other. Cadmus warns Pentheus early on:

Remember Actaeon, how he died? His darling dogs, whom he himself had fed, ripped him apart in the hills, and ate him raw, because he boasted he could hunt better with hounds than Artemis. Don’t share his fate!

(Eur. Bacch. 337-341, trans. Emily Wilson)

Pentheus does very much share his fate as he is ripped limb from limb by his mother, aunts, and the women of Thebes.

Euripides here gives an iteration of Actaeon’s myth that echoes Pentheus’ with an insult to a powerful and wild god being the catalyst for downfall. In Actaeon’s case this is Artemis, in Pentheus’ it is Dionysus.

Further, their deaths occur at the same spot on Mount Cithairon. Cadmus describes it as

Where once the hounds ripped Actaeon between them.

(Eur. Bacch. 1291, trans. Emily Wilson)

Illustration: C. Kappely

It is interesting too that both of their deaths involve a kind of animal transformation. Euripides does not mention it but the reason for Actaeon’s hunting dogs killing him is that Artemis has transformed him into a stag.

Similarly, Pentheus at the moment of his death is no longer human in the eyes of his aggressors. Agave believes she is killing a mountain lion and does not recognise him as her son until much later (1170-1180).

From the connection that Euripides makes between Actaeon and Pentheus we can see Artemis and Dionysus as gods with the power to destabilise the boundaries of identity. They were not figures I had previously associated with each other but they are clearly linked in interesting ways.

Overall, working on Bacchae for MANTO gave me new insights into the text and was a wonderful excuse to further dissect this play that I adore.

Thank you to Greta Hawes for the opportunity and the freedom to work on a text of my choice. I learnt a lot and had a wonderful time!