Episode 32: Helen of Sparta, Helen of Troy

Welcome to another episode of the Greek Myth Files! In this installment, we treat the complicated and varied figure of Helen of Sparta, who was famously seduced by the Trojan Paris. When she left her husband Menelaus, he called upon the heroes of Greece who were suitors to fulfill their oath to protect the couple and to avenge any wrongs perpetrated on them. Here, we’ll cover Helen’s family, her birth from an egg, her abduction by Theseus, her marriage to Menelaus, her seduction at the hands of the handsome Paris, and the guilt she feels while in Troy.

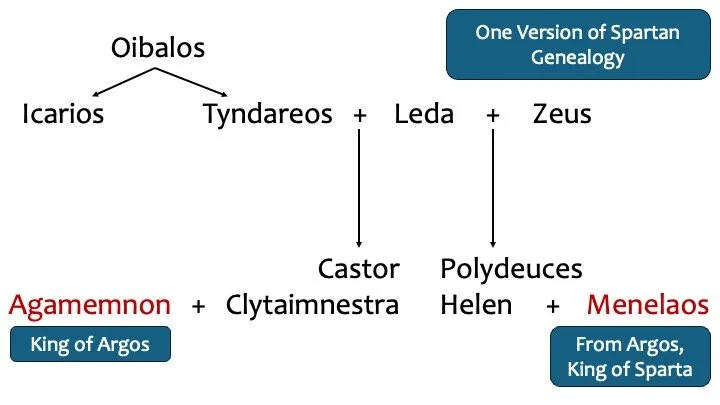

In order to understand the genealogy of Sparta (and all the names in the episode), we’ll provide a genealogical chart below.

Helen’s conception and birth are unusual and complicated, with a substantial tradition that makes her the child not of Leda but of Nemesis, the goddess of retribution, and born from an egg. This version is famously told in Pausanias’ description of the sanctuary of Nemesis in Rhamnous north of Athens:

§ 1.33.7 Neither this nor any other ancient statue of Nemesis has wings, for not even the holiest xoana of the Smyrnaeans have them, but later artists, convinced that the goddess manifests herself most as a consequence of love, give wings to Nemesis as they do to Eros. I will now go onto describe what is figured on the pedestal of the statue, having made this preface for the sake of clearness. The Greeks say that Nemesis was the mother of Helen, while Leda suckled and nursed her. The father of Helen the Greeks like everybody else hold to be not Tyndareus but Zeus.

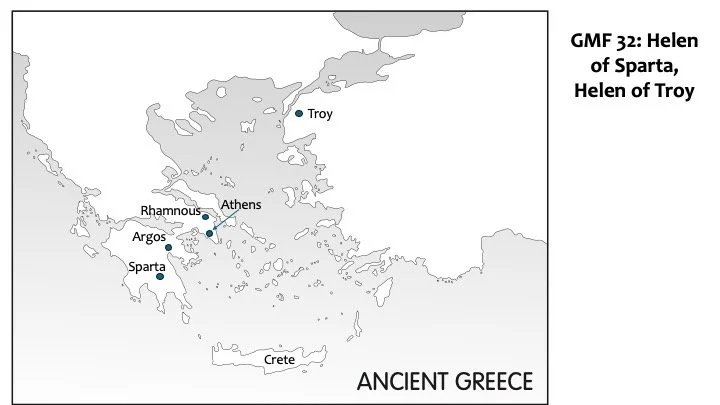

To help conceptualize the places in the podcast, here is a map:

Most visual depictions, however, have Zeus seduce Leda in the form of a swan (who would then lay the egg of Helen), as seen in this vase:

With Zeus and Aphrodite in the register above, Zeus in the form of a swan seduces Leda (named) while Hypnos (Sleep) watched on from the right. From Apulia (Italy) around 330 BC, now in the Getty Museum.

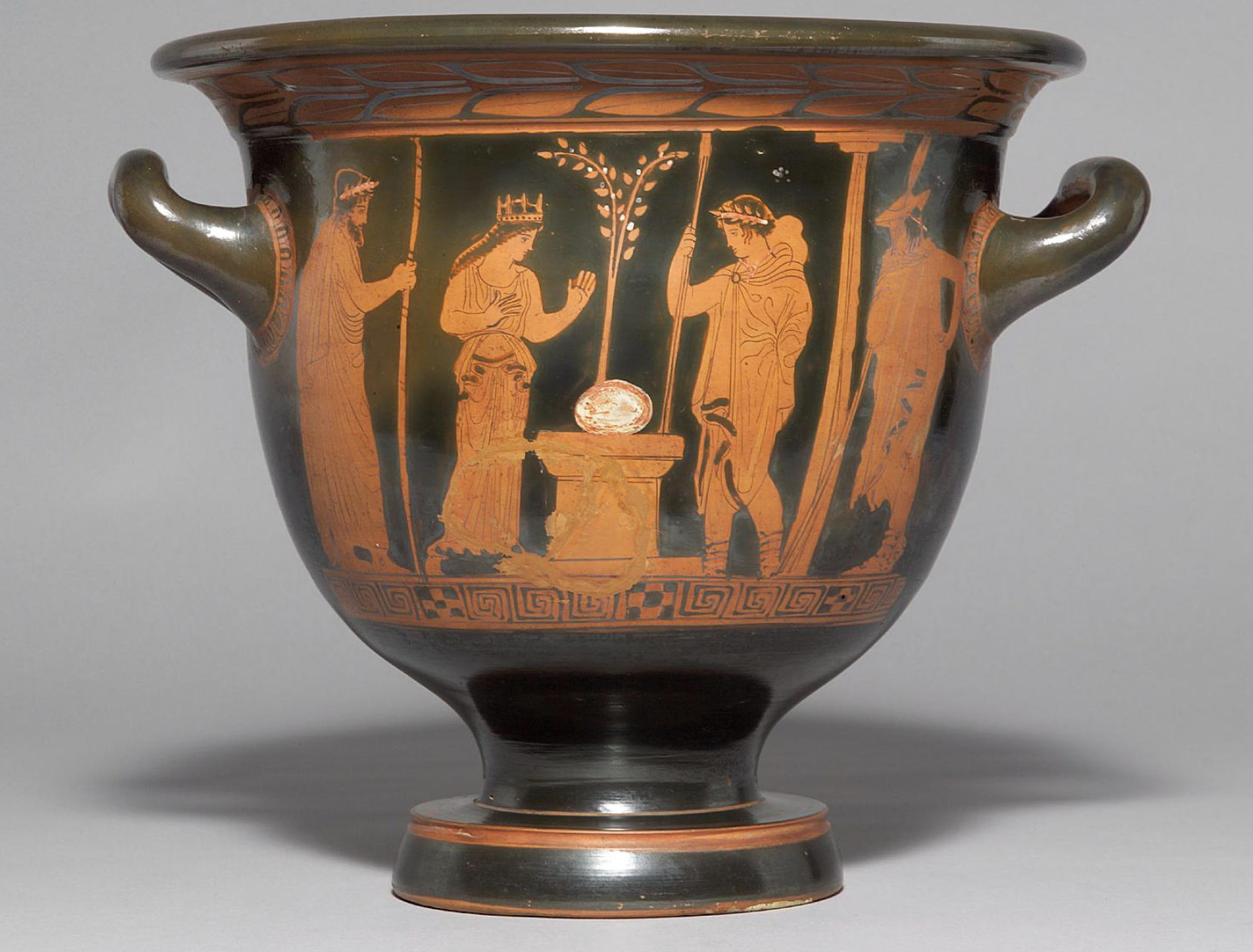

The egg features prominently in vases as well. Here, the egg is between Leda and her mortal husband Tyndareos.

The egg from which Helen will emerge sits on an altar, with Leda and Tyndareos watching on the left, and the Dioscuri on the right. Note this complicates the genealogy found in many sources that Helen was born at the same time as the Dioscuri. The vase from around 410 BC and of unknown provenance is now housed in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

The famous oath of the suitors given by Tyndareos is found in the Hesiodic Catalog of Women. A substantial portion of the list of suitors and the oath is found in a papyrus from the third century A.D. (from Hermoupolis) . The passage given below is fragment number 204 in the edition of Merklebach-West and describes the oath and Menelaos’s winning of Helen because he offered the most gifts—though the poet is clear to note that if Achilles had been one of the suitors, he would have won her hand. We’ll return to Achilles and discuss how his non-suitor aspect plays out in the Iliad in a later episode.

]for the sake of the maiden

]he asked all the suitors for reliable oaths

and he ordered them to swear and [a word missing] to vow

with a libation, that no one other than himself should make other plans

regarding the fair-armed maiden’s marriage; any man

who would seize her by force, and set aside indignation and shame,

he commanded all of them together to set out against him

to exact punishment. They swiftly obeyed,

all hoping to fulfill the marriage themselves; but [all of them

Atreus’ son [defeated], warlike Menelaus,

for he offered the most. Chiron on wooded Pelion

was taking care of Peleus’ swift-footed son, greatest of men,

who was still a boy; for neither warlike Menelaus

nor any other human on the earth would have defeated him

in wooing Helen, if swift Achilles had found her still a virgin

when he came back home from Pelion.

But warlike Menelaus obtained her first.

Menelaos marries Helen and becomes the king of Sparta. Paris, however, seduces Helen and takes her back to Troy. Note that in no early version of the myth does Paris abduct her against her will. A really neat vase that shows the seduction of Helen by Paris on one side, and Menelaos reclaiming her after the war on the other, is found in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

Was Helen guilty? That’s the million-dollar question and the one that was the most commonly discussed aspect of the myth in antiquity (and today). In the Iliad she is definitely conflicted, now critical of Paris, now falling for him again. She refers herself in negative tones and recognizes her role in the whole affair. One common variant was that Helen never went to Troy at all! Instead, it was only an image of Helen who went, while Helen herself hung out in Egypt during the whole war.

One of the great scenes from ancient tragedy is the famous “court” scene in Euripides’ Trojan Women. That’s a very sad play that dramatizes the distribution of the Trojan Women to Greek kings as warprizes and the death of Astyanax, the son of Hector and Andromache. Toward the end of the play, Menelaos comes to on the scene and demands Helen. He’s inclined to kill her for her infidelity and for causing so much loss in war, but he gives her the chance to plead her case. Then, Hecuba, the queen of Troy, offers a counter-argument to Helen’s points. Summarized:

Helen: 1) Hecuba’s the responsible one because she gave birth to Paris even though she had a dream that he was going to cause the war bring destruction to his city; 2) it’s good that Paris chose Aphrodite, who offered me up, because otherwise the Trojans would have conquered Greece (since that’s what Hera offered him); 3) Menelaus, you left me alone with Paris and he took advantage of me! 4) Aphrodite is really to blame; and 5) afte Paris’ death I really tried to escape but my new husband’s guards kept watch over me.

Hecuba: 1) don’t blame the gods for your infidelity—people often use gods as pretexts for their own actions; 2) when you saw how luxurious and wealthy Paris and the Trojans were, you leapt at the chance to life the easy life; 3) abducted? really? Why did you not cry out? Your hero brother Castor and Polydeuces were around and would have saved you; 4) during the war, you favored the man from whichever side was winning at the moment—you hedged your bets! 5) If you were really desperate to leave Troy, you could have committed suicide as any noble woman would have done.

The outcome? Menelaos had every intention of exacting revenge from Helen, but when he put her on the ship her charms worked on him and she lived happily every after with him (as seen in the Odyssey).

As mentioned in the podcast, there is a significant scholarly tradition that Helen was originally a goddess based on comparison with mythical patterns in other ancient cultures. It’s complicated and a lot, so we suggest anyone who wants to see the whole argument on both sides take a look at Lowell Edmonds’ full length account that’s available online.