The Journey of Recording Greek Mythology in MANTO: Armour Edition

written by Ruby Woodbury

This semester I got an opportunity to work collaboratively with Greta Hawes and other Macquarie University students as a PACE intern on MANTO. Guided by Greta’s wisdom and the assistance of Anika Campell, we were tasked with entering certain artifacts from the Gdańsk Decorated Armour Database (DAD) and Digital LIMC into MANTO’s database. We predominantly focused our time on entering around 130 (mostly) fragmented shieldbands recovered from Olympia.

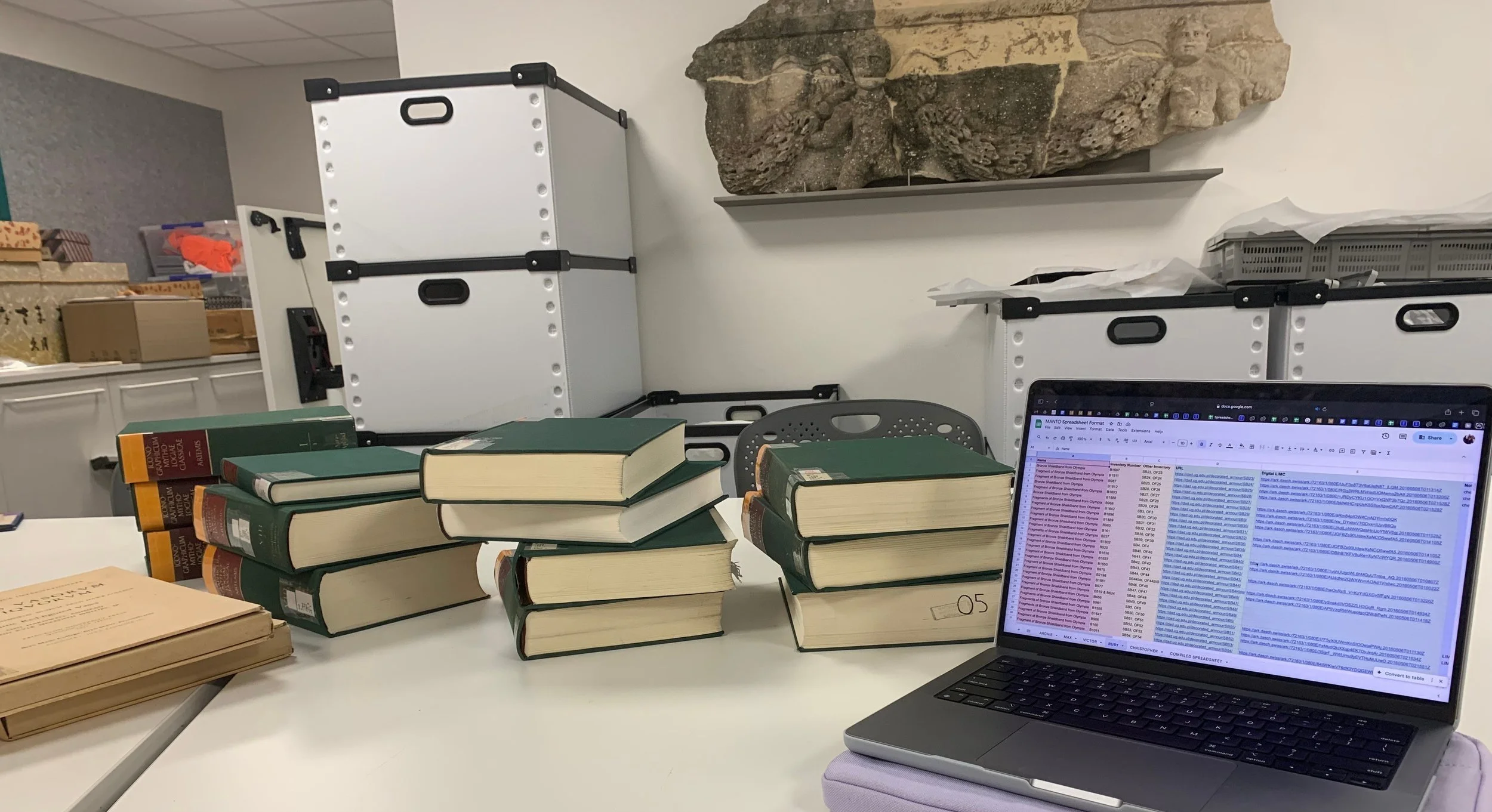

Macquarie PACE internship, day three.

Image: Ruby Woodbury

I have always been fascinated by Greek mythology due to my love of culture, religion and narrative. However, to say that initially the thought of working with a digital database was intimidating would be an understatement. I had little experience working with or navigating databases and overall my confidence with technology was low. However after working within this internship, I was able to gain major confidence with working with and navigating different digital databases, while also delving into my continued interest in Greek mythology.

One of the biggest difficulties I found with working with some of the shieldband iconography is the amount of corrosion and fragmentation. A few of these pieces remain in good condition and are well photographed, like the fragment in the Getty (below) on which we can easily recognise Menelaos recovering Helen in the top panel, and Deianeira being carried off by the centaur Nessos below (many of the characters have their names inscribed beside them). But these well-preserved panels are rare.

Fragment of a shieldband signed by Aristodamos of Argos, ca. 575 BCE. Getty 84.AC.11.

Author: Getty open content program via Wikimedia Commons

Although we were advised not to make our own decisions about the iconography on the shieldbands, sometimes we did have to work out whether significant weapons or other items, or specific locations, were depicted. This could be extremely difficult. Despite these iconographical issues though, I did find certain aspects of these iconography interesting to see. For example, on shieldband metapes depicting Heracles fighting the Nemean Lion, determining whether or not Heracles is holding a sword, club or nothing was sometimes a struggle. Often we could not make these distinctions in MANTO’s data. What I do find interesting though is that Heracles in the end usually killed the Nemean Lion barehanded, because he was unable to penetrate its skin with a weapon. Some ancient sources (like Apollodoros 2.5.1.) don’t even mention Heracles using a sword to attempt to kill the lion, only a club and bow and arrow. Nonetheless, it was common to find Heracles depicted using a sword on these shieldbands. So seeing these different interpretations of the myth within the iconography is fascinating and can be interpreted as either different tellings of the myth or a progression of the myth where Heracles uses his sword or club first and then switches to strangulation.

A similar problem occurred in dealing with Zeus fighting Typhon, where we had to determine if Zeus was holding a lightning bolt or not (most of the time we just give him the benefit of the doubt). However I must say, Typhon’s monstrous figure was always so cool to see depicted on a shield band. (The image on the hydria below is similar to the depictions on shieldbands when they aren’t too fragmented or corroded.)

Zeus fighting Typhon, as depicted on a black figure hydria, Staatliche Antikensammlungen, no. 596.

Image: Bibi Saint-Pol, via Wikimedia Commons

With the birth of Athena, it could be difficult to determine whether Hephaistos was present in the image or not. Now this myth is awesome to see, if it is clearly depicted, as Athena is born from Zeus’s head after Hephaistos splits it open with his axe. Unfortunately, some shieldbands are so damaged that the figures can be difficult to make out. This was probably one of the ones that gave me the most grief, as both B1687 and B1911 had the exact same iconography and issues: the axe of the Hephaistos is claimed to be there, but he himself is not visible and the Throne of Zeus is visible, but not Zeus himself. It left big gaps of details that I wasn’t sure how to fill without compromising accuracy.

One of the myths that I found especially fascinating was the depiction of Zeus, who had taken the form of a bull, abducting Europa on shield band B315 and possibly B985. The iconography of the Europa myth was unusual in this corpus, and it begs the question, why would someone put this myth onto a shieldband? Then again, a lot of mythological iconographies on these shields bands confused me, the reason being because the wide assortment and variety of shieldband iconography ranging from different mythological depictions, to scenes of lions, gorgons, sphinxes etc, which suggests that the warriors who owned these shieldbands most likely got to choose what they wanted depicted. This idea is supported by the DAD website. So that leaves the big question, what reason would someone have to get the abduction of Europa on a shield band?

Mosaic depicting Europa being carried away by Zeus who had fallen in love with her and turned himself into a white bull in order to kidnap her from her family and take her to Crete. Gaziantep Zeugma Museum.

Image: Dosseman, via Wikimedia Commons

In this context, some scenes, like Heracles fighting the Nemean lion and Zeus fighting Typhon, Heracles fighting Geryon, Heracles fighting Apollo over the Delphic Tripod, Heracles capturing the Erymanthian boar, Achilles killing Troilos etc, make sense to me as they depict famous combats which is relevant to the use of the shieldbands. Even depictions of the birth of Athena make sense, as she is the goddess of battle and strategy, so including her on a shieldband might bring luck in battle.

But I could not understand other common iconographies of these shieldbands, such as the numerous bride abductions, the abduction of Helen or even worse the rape of Cassandra at the Palladion. I know you can sometimes make the connection to Helen’s abduction to the beginning of the Trojan war, but a lot of the Helen abduction shieldband iconographies show Theseus and Pirithous kidnapping Helen, which does not have any connection to battle or war glory that other common shieldband iconographies have. The same with the raping of Cassandra, I just don’t understand the purpose or reason behind this depiction, when something more fitting to actual combat would be more appropriate.

This is why I came to see each shieldband as not only depicting a mythology, but also what the warrior who owned it may have valued or believed in the most. This made the process of putting these shield bands into MANTO all the more fascinating to do, because it made me reflect and think about the warriors who have owned and used these shieldbands and what they may have valued. And sadly, although I wasn’t entirely expecting some of these types of myths to have been depicted, it also doesn’t surprise me in hindsight, especially with what we already know of the values of ancient Greek men during the BC period.

Overall I believe that not only were we successful in contributing to MANTO’s growing database of Greek mythology, but I was also able to gain major skills and confidence in working and navigating digital databases and enhancing my referencing skills, which I believe will benefit me in the future.

This is the second in a series of blog posts from students at Macquarie University who are participating in this semester’s PACE internship.