A dataset of mythical people with stable URIs

Written by Greta Hawes & Scott Smith

MANTO began as an attempt to map mythic space. And yet we quickly learned that while places are relatively well catered-for with digital tools like Pleiades and Recogito, our biggest challenge was that no one had yet created an authoritative digital dataset for the names of mythical characters. And not only was there no digital dataset, none of the existing encyclopedias—Roscher’s Lexicon or Smith’s Biography or Pauly-Wissowa’s Realencyclopädie—had these names organized in a way that quite suited our needs, or agreed on a “canonical” order for them that made for easy digitization (more on this here)

And so we had to start from scratch, a process that would be incremental and involve re-litigating a lot of decisions about individual entities—a reminder that the contested space of the Greek mythical storyworld, and our partial evidence for it, is messy and cannot be easily contained and set into a digital ontology.

Our first iteration of the dataset is now finished, and available to explore. It contains 3618 people, including all those named in Homer’s Iliad, Hesiod’s Theogony, Apollodoros, and Pausanias: a critical mass covering the most common figures and many of the rarer figures that populate the edges (at least those edges that we can see). The dataset is stable: each entity is paired with a unique URI (more on this below); we hope that this will be a useful resource for others as well.

The dataset will of course continue to grow as we add further texts to MANTO. But at this juncture in the project, we wanted to dedicate a blog to describing the way that dataset was constructed, and its structure.

Our process, to be frank, was not entirely thought through at the beginning, not that having done so would have saved us time or headaches. Our goal at the outset was to choose those texts that would give us the biggest mythological bang for our efforts: Apollodorus’ Library was the obvious choice since it is the most comprehensive view of the mythical storyworld. So we began by uploading to our database a list of people based on the index to Smith & Trzaskoma’s translation of Apollodorus, which of course had some consequences. Most visibly, we followed their transliteration scheme (hence Greek transliteration, but using “c” for “k” unless the results looked weird in English — e.g., Dike not Dice, Nike not Nice, Kore not Core). We plan to eventually add the original Greek and Latinized names, as well as a more systematic list of alternative spellings.

To the Apollodorus, we then added Homer’s Iliad, Hesiod’s Theogony and Pausanias’ Description of Greece, which, when entered, gave us a solid foundation of entities. The index of names for Pausanias was created by Smith, who collating the list of names in the critical edition of Rocha-Pereira with the existing names in the MANTO database, making corrections where necessary. This saved a great deal of time during data entry, since the numerous local figures did not have to be added during the collection process. To give an indication of magnitude, of the 3618 people in the databast, 1809 are mentioned by Pausanias, and many of those only by him.

Crucial to this process has been Roscher’s Lexicon, a massive encyclopedia of myth compiled 1884–1937. This provides detailed discussion of figures and, most importantly, a reasonable division of entities that guided our decision-making. Because Roscher’s articles also attempt to give a comprehensive list of ancient passages where the entities were found, we could consult most of the available data to make final decisions when to assign a data point to an existing entity or create a new one. We hope that this will mean there are many fewer '“surprises” as we continue to add more texts.

Unique Identifiers

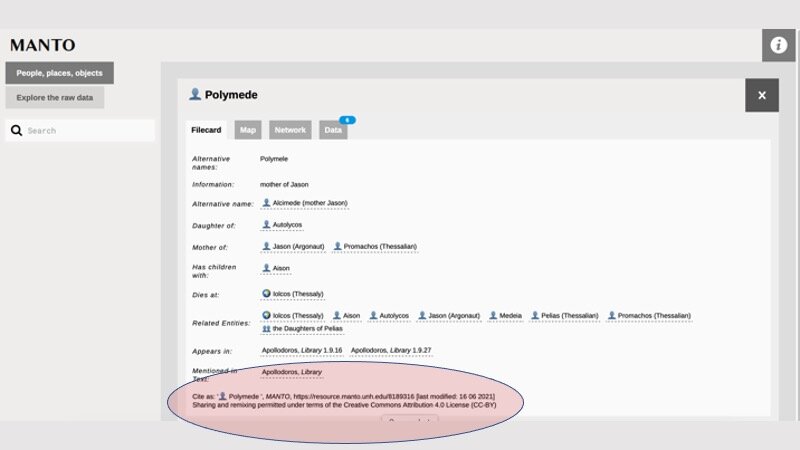

Each entity in MANTO now has a stable URI. These are the ‘Object IDs’ that appear as the final digits of the URL in the interface (e.g. 8188822 for Theseus). At the bottom of each filecard is the canonical URL for that entity (e.g., for Theseus, https://resource.manto.unh.edu/8188822). The API can be queried at https://api.manto.unh.edu/. We can also provide .csv files of this data, in various configurations, just get in touch.

You can find the citation details, with canonical URL, at the bottom of each filecard in our interface.

With all this being said, distinguishing one mythic character from another is a tricky business, as Scott’s posts on the topic (here and here) have shown. At the most basic level, even the most secure mythical figure has unstable data points, many have varying genealogies, and some eponymic entities have wildly different natures (like the four figures named “Psophis”—males and females—to explain the name of the town). Where it is not possible to strictly disambiguate characters, we have developed a series of methods for expressing ambiguity and uncertainty; we freely admit that we are not always entirely consistent in how we deal with similar situations, which require individual examination, discussion, and—most importantly—a practical solution that is suitable for a digital ontology.

Alternative names

Lots of characters in myth have more than one name: the Trojan Paris, for example, is also called Alexander in the Iliad and elsewhere. In his case, as so often, the existence of different names makes no difference in the networked connections we are building up, so we simply list the two names against the same entity. However, there are instances where we are forced to break our ‘one person = one entity’ rule to capture alternative names that forge significant connections. In these instances, we create an entity that exists only as ‘alternative name for’ a main entity. A good example is Neoptolemos, the son of Achilles, whose other name, Pyrrhos, was given to him by Lycomedes (Paus. 10.26.4), and it is under this name that he is remembered as (a possible) eponym for the Greek town Pyrrichos (Paus. 3.25.1–2).

Possibly the same as

Where we just don’t have enough information to decide that two entities are definitely the same, or (on the other hand) to rule out this possibility, we link the entities together using the connection “possibly the same as”. For example, there is the unique reference to a Cretan Talos, son of Cres, in Pausanias which is perhaps supposed to be understood as an allusion to the more famous bronze Talos of Crete but without more context we cannot be sure. This is a good solution for the notorious problems of Iliadic “cannon fodder” (e.g.: two Phocians called Schedios, both killed by Hector; the two (or three?) Pylians called Alastor); it also clarifies (possible?) intertextual allusions: at 3.12.5 Apollodorus names Priam’s (many) sons, three of whom are perhaps supposed to recall Trojans whose deaths are described by Homer but without the requisite genealogical data (see Aretos, Deiopites, and Hypeirochos).

Sometimes conflated with (and a practical solution to insoluble issues)

Ancient authors frequently disagreed over exactly how many heroes there were with the same name as well. By way of example, we can point to the case of two figures called Nauplios, one the son of Poseidon and Amymone who gives his name to the city of Nauplion, the other — several generations later — one the son of Clytonaios and father of Palamedes who avenges his son’s death by shipwrecking the Greeks as they sailed home from Troy. Apollodorus, however, argues that these are in fact the same “extremely long lived” figure (2.1.5). In this case, the note “sometimes conflated with” appears on the entities’ filecards, and you can search in the data tab for ‘“is conflated with” to find the passages where this happens.

Where the opposite situation applies — i.e. a figure is usually treated as singular, but an ancient source argues that it should in fact be two — we decided that creating two separate figures would result in a hopeless situation and so that best solution is to create one entity and let the data speak for itself. The case par excellence for this is Atalanta, who has a Boiotian and Arcadian presence, often with different genealogies, but the conflation (if in fact it is conflation) or confusion (if in fact it is confusion) is so persistent that data collection would be rendered problematic because we’d have to assign a data point to one or the other, often at random. Where necessary, we have provided notes in the “Commentary”.

Rationalizations

As Greek writers subjected their mythical traditions to scrutiny, they sometimes rationalized the unbelievable aspects of the stories. (There’s a great discussion of the topic in The Greek Myth Files ep. 8.) This process can result in the creation of a “separate” entity from the one that features in the standard version. We only add these to our dataset where strictly necessary. One good example is king Aidoneus who is said to have captured Theseus and Peirithous but who obviously serves as a rationalization of Hades (who had the epithet Aidoneus) to allow for an historicized version of the two heroes’ imprisonment in the Underworld. In Plutarch’s account (Life of Theseus 31–35), we also find Kore as the name of the daughter of Aidoneus and Phersephone, so we have to list both Kore and Phersephone as rationalized forms of the mythical Persephone (who has “Kore” as an alternative name!). Because these create new genealogical connections and other associations, it is necessary to create them as new entities.

Identified with

Understanding how (or if!) gods in one culture might correspond to gods in another is a complicated matter. We have added some Roman equivalents of Greek gods as alternative names to aid search functionality (try '“Juno” or “Venus”).

Where one of our sources explicitly says that a non-Greek figure is equivalent to a Greek one, we have captured that as an assertion. These appear on the filecards as “Identified with”. You can find the passage where the assertion is made by searching the data tab for “is identified as”. One current example is Maceris, whom Pausanias describes as the Libyan equivalent of Heracles.

Transformed from / into

On our filecard we also note transformations, but only when one entity is said to be metamorphosed into another entity with a distinct enough identity to warrant a second entity. So, while we capture “Daphne is metamorphosed” we do not create generic items like “laurel tree;” the tie is simply to announce that a metamorphosis takes place. But take, for instance, Cainis’ transformation into Caineus, or when Melicertes become the god Palaimon. In both cases, though more clearly in the latter, the activities of each entity is different and necessitate two entities that can be treated either separately or in combination.